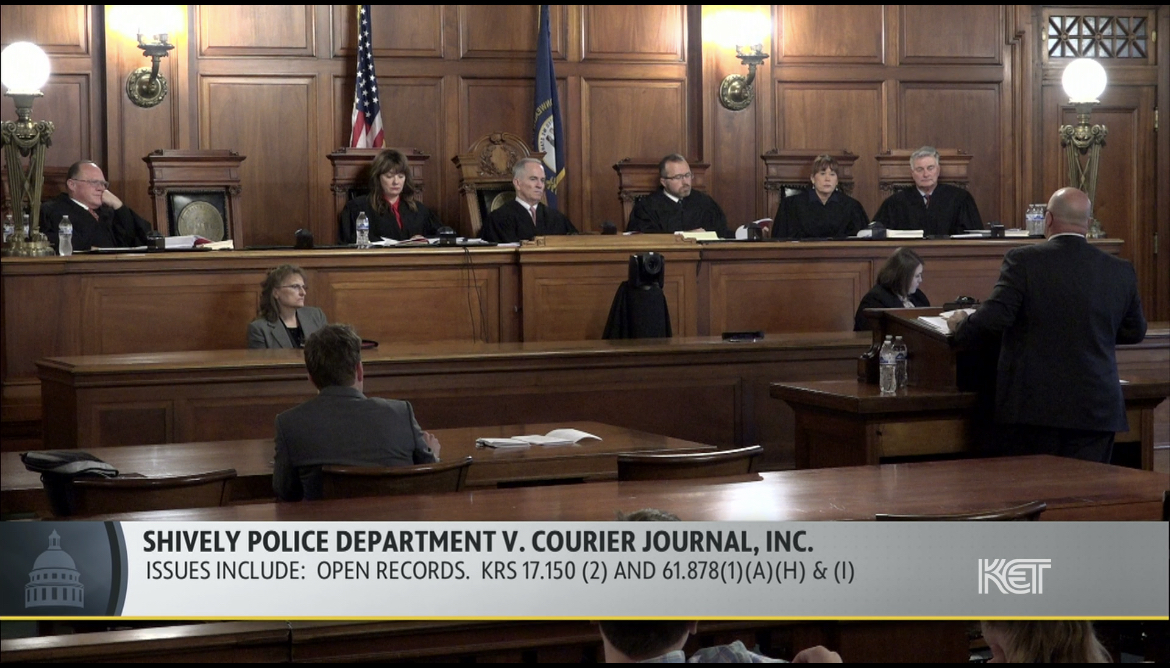

Shively Police Department v Courier Journal, Inc. became final earlier this month. It is now controlling legal precedent in Kentucky. Law enforcement agencies that elect to ignore it, do so at their peril.

http://opinions.kycourts.net/sc/2023-SC-0033-DG.pdf

We have seen some movement in the right direction in the aftermath of the Kentucky Supreme Court's September 26 opinion. That opinion restored the original legislative intent of the open records law and returned to law enforcement agencies the burden to sustain their denial of open records requests by proof -- and not by the mere statement that a case is open.

For example, we know of a requester who was originally denied access to virtually all records in an "open" case involving a fatal accident. She resubmitted her request, this time citing Shively Police Department v Courier Journal, Inc. She later received a number of records that the law enforcement agency had previously withheld.

But old habits die hard. The same agency continued to cite KRS 61.878(1)(h) and KRS 17.150(2), arguing that releasing other records could harm the outcome of the ongoing investigation and prosecution.

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=54126

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=46877

As word spreads of this "watershed" Supreme Court opinion, local government support groups -- like the Kentucky League of Cities -- are reaching out to their constituencies with guidance on the legal duties clarified in Shively Police Department v Courier Journal, Inc.

https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/local/2024/09/27/kentucky-su…

On October 22, KLC issued an overview of the case and identified three key takeaways. The update, authored by municipal law attorney Megan Griffith, continues to characterize KRS 17.150(2) as an exemption -- erroneously, we believe -- but otherwise provides useful direction.

https://search.app/QFonfWNxSC8crjbM6

• We concur with the first of KLC's key takeaways:

"Justification of Exemption Must Be Concrete: The court emphasized that a broad denial of records is not enough. When citing the law enforcement exemption, agencies must provide factual basis illustrating how the release of records would pose a concrete risk of harm to their investigative or prosecutorial efforts. General concerns about witness statements or grand jury tainting, as claimed by Shively Police Department, were deemed insufficient.

"When considering whether to invoke this exemption, ensure that your rationale is clear, detailed, and directly tied to the content of the records. Blanket statements of hypothetical or speculative harm without supporting evidence won’t meet the legal standard. Supporting documentation, like an affidavit, must provide details of concrete harm to the investigation if the records are subject to public disclosure.

• We disagree with KLC's second key takeaway to the extent it suggests that KRS 17.150(2) is an "exemption" that can be invoked while an investigation is open or prosecution is incomplete. It is instead accurate to state, as KLC ultimately does, that the Supreme Court rejected Shively Police Departments's reliance on 17.150(2), "stating that the statute applies only after a prosecution is concluded or a decision is made not to prosecute" and that it "pertains to the disclosure of intelligence and investigative reports post-prosecution. Any suggestion that KRS 17.150(2) might be invoked to deny access to "records during an active investigation [by] demonstrating a concrete risk of harm" misinterprets the Supreme Court's opinion.

KLC more correctly states:

"Contrary to decades long guidance issued by the Office of the Attorney General, this case now finds that KRS 17.150(2) is not a tool for withholding records while a case is active. City officials should apply this exemption only once a prosecution has been resolved or a determination not to prosecute has been made."

• We agree with KLC third takeaway and the Court's reminder:

"There is a Duty to Separate and Produce Nonexempt Material: The court also reviewed the 'personal privacy exemption' (KRS 61.878(1)(a)) and determined that SPD didn’t adequately justify withholding all footage on privacy grounds. While the Court acknowledged that certain images (like those depicting the deceased) could be sensitive, it held that other portions of the footage should be disclosed. The Open Records Act requires that if any public record contains material which is not excepted, the public agency shall separate the excepted and make the nonexcepted material available for examination. (KRS 61.878(4)).

"Moving forward," KLC urges official to "provide more specific justifications when withholding records under the law enforcement exemption [and] ensure partial disclosure when possible...when faced with open records requests related to open investigations."

KRS 17.150(2) is off the table, altogether, until prosecution has been concluded or the decision not to prosecute has been made. It is emphatically not an exemption to public access but instead a mandatory investigative and intelligence reports disclosure provision -- triggered by concluded prosecution or the decision not to prosecute -- that contains four carve outs for records that may be withheld. "The burden shall be upon the custodian to justify the refusal of inspection [under one or more carve out] with specificity" if such records are withheld after prosecution or a decision not to prosecute.

https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=46877

Given the referenced post-Shively partial denial of the resubmitted open records request, still citing KRS 17.150(2); KLC's perhaps unintended but erroneous mixed messaging about KRS 17.150(2); and the inevitable bureaucratic inertia that accompanies such an important restoration of the original laws -- both KRS 61.878(1)(h) and KRS 17.150(2) -- we are apt to witness additional public agency backsliding on this critical open records issue.

And, of course, we must prepare ourself for a potential legislative response and ensuing battle. January -- and the start of the 2025 Regular Session of the Kentucky General Assembly -- is only a few months away.